Obituary – Major Tom Bird DSO, MC

Obituary – Major Tom Bird DSO, MC

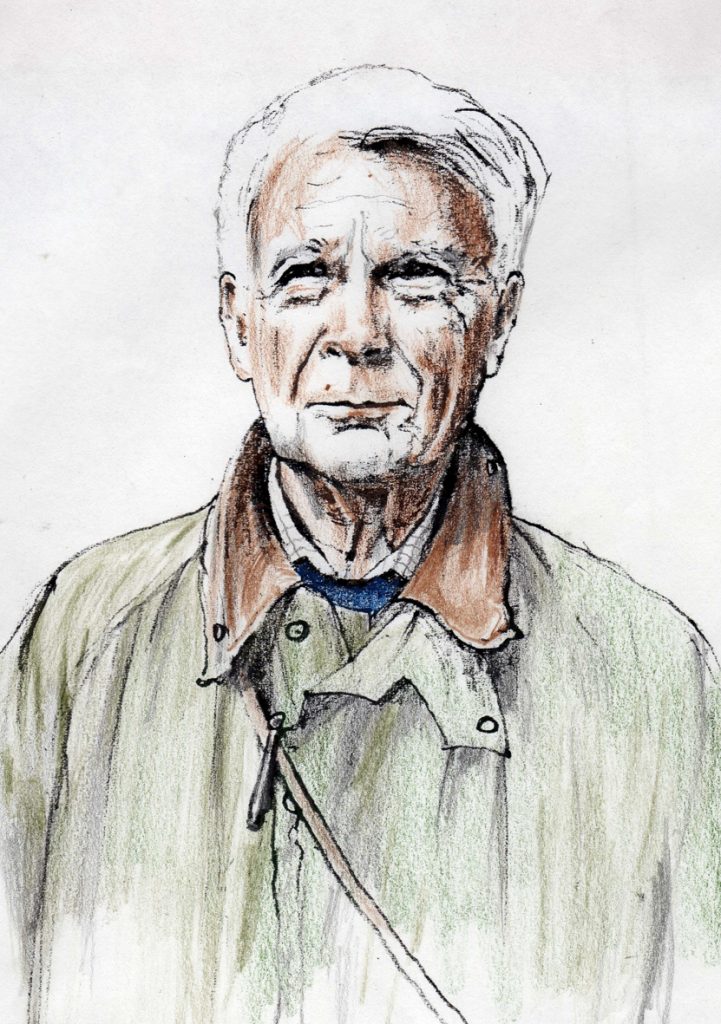

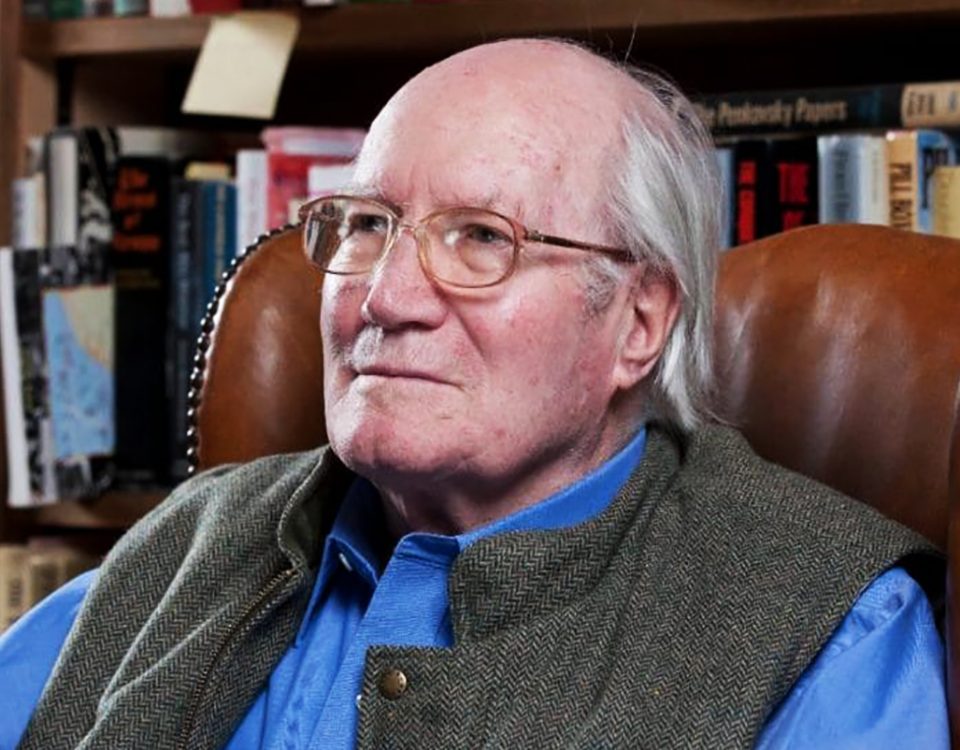

MAJOR TOM BIRD DSO, MC, veteran of Alamein and the Desert War (father of Nicky and grandfather to young Tom Bird), died aged 98 at his home in Turville Heath on August 9, where he had lived for 40 years. He was born and brought up in nearby Fawley, and was very much a man of the Chilterns, who rode its paths and walked its valleys and woods. He was a fine sportsman, perhaps on his day the best shot in the country. He played cricket at a better level than us, skied and climbed in the Alps, played good tennis and passable golf, and played excellent bridge but better before dinner than after. He turned out for the V&A on numerous occasions when we were short – and last played at Turville about 15 years ago (see photo). For two years he opened the batting for Winchester College; he played for MCC, Free Foresters, Butterflies and his county, Berkshire. He would have stepped up a league but his architectural studies and Herr Hitler intervened. He once played for Henley against a Plum Warner MCC team that featured the Compton brothers. Dennis arrived with a pretty girl. He got himself out first ball so he could go and enjoy her in the woods. Leslie Compton, who was floozieless, made a ton.

After the war he set up an architectural partnership with a fellow Desert Rat, Richard Tyler. Bird designed and remodelled many classical country houses, including Hall Barn outside Beaconsfield for Lord Burnham. Country Life called his neo-classical houses ‘dignified and well-proportioned’. He was High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire in 1989.

Bird was a modest soldier but was one of those rare men that actually turned the tide of battle. At the height of El Alamein (Oct 23 – Nov 24, 1942) Bird’s regiment, 2nd Rifle Brigade, was in a small depression 2000 yards in front of the British forward position, codenamed Snipe. On October 27 Rommel threw his armour at the beleaguered battalion, but throughout the heat of a long day Bird’s anti-tank company, which he commanded, destroyed and stopped all the advancing German and Italian tanks. The action saved Monty’s bacon; the battle had been going badly.

At first light on the 27th Bird had stood in the open, desperately repositioning his new 6-pounder guns so they had good fields of fire. He was lucky to survive this blatant action; his second-in-command was killed. But at midday a crisis developed, and the battling rifleman of 2RB seemed about to be overwhelmed – some 6-pounders were knocked out and those that could fire were out of ammunition. Enemy tanks lurched forward. Rifleman R.L. Crimp, who later published his diary account (Diary of a Desert Rat, 1974), saw what happened next –

‘Several guns are now completely out of ammo. The situation’s so bad that two officers of ‘S’ Company [Bird and a platoon commander], try to effect a re-distribution of what remains by jeep. They travel slowly over the dunes (four-wheeled drive carrying them on), quite heedless of the M/G bullets slashing the air around them and panzers potting straight at them, collecting odd rounds from knocked-out guns or the guns of knocked-out crews, and taking them to guns that can still strike back. One bullet amongst the ammo on board and the lot would go sky-high.’

The battle raged on until nightfall, but this drastic action had saved the battalion. It prevented Rommel crashing through the British lines causing havoc. Without it, the Battle of Alamein could have been very far from the decisive victory, Churchill’s ‘end of the beginning’, that we celebrate.

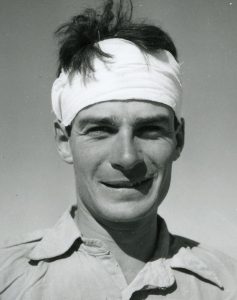

Bird, ‘an inspiration to all ranks’ was awarded the DSO for ‘his courage and leadership’ (his men thought it should have been a VC). The citation continued: ‘Major Bird paid no heed to his own safety… He was always at the critical point… directing the fire of a gun whose No. 1 was wounded, loading another… fetching ammunition and cheering his men. All this he did under intense fire’. At the height of the battle Bird, always crippled with shyness, had promised himself that if he survived he would never go to another dance. But he did. His American wife, Alice, who died in 2015, loved dancing.

When the battle was over he felt no elation. ‘Friends lay dead and we had lost all our guns; all my officers had been killed or wounded…it didn’t seem to me like a great victory.’ But it was. The enemy had lost about 60 irreplaceable tanks, self-propelled guns and artillery pieces, to 300 riflemen. Newspapers back home called it ‘the finest action of the war’. Bird himself was wounded in the head towards the end of the day, struggled on but eventually collapsed.

Years later, Nicky Bird was publisher at the V&A and produced a jigsaw of the Snipe action by Terence Cuneo. He asked his father whether in the noise of battle he had thought that ‘this would make a jolly good jigsaw’. ‘No’, he said, he had stupidly failed to see its potential.

Before Snipe, Bird was already a desert legend for his aggressive night patrols, and for capturing an astounding number of Axis prisoners. He had won 2 Military Crosses. One of his Battalion’s riflemen, Victor Gregg, called him ‘a man of exceptional courage. When all seemed to be lost, there would be Dicky boy, calm and seemingly aloof from the dangers around us…’ [Rifleman, 2011]. His most daring escapade was leading a relief column of ammo and guns into the Free French desert citadel of Bir Hikeim (July ’42). He had to sneak through German lines. He got away with it, just. On coming out at night his lead truck hit a mine, and the whole column was lit up. He described the moment as ‘alarming’ – which translates from army understatement as ‘bloody terrifying’. The grateful French eventually awarded him a Légion d’honneur for his gallantry, at a reception at the French embassy in London. The Ambassador embraced him and kissed him on both cheeks, an ‘ordeal worse than battle’ Bird said. Of his many other honours, none of course chuffed him so much as being the first Vice President of the V&A Cricket Club.

Recuperating from his wounds at Alamein, he served as ADC to both Field Marshal Wavell (whose son was a friend) and FM Auchinleck in India before returning to his regiment. He was blown up by a mortar during 30 Corps’ drive to Arnhem in September 1944, and dragged to safety by the present Lord Saye and Sele. His fighting war ended. He served with distinction in Washington as ADC to FM ‘Jumbo’ Wilson, where he dined with Mountbatten and the Duke of Windsor and was privy to the date of D-Day and the secret of the atom bomb – both secrets he would have preferred not to know as he tended to talk in his sleep. He met most of the great names of the war. He spent a day with Eisenhower in Potsdam mending a fountain, joked with Churchill, hobnobbed with Roosevelt and Stalin at Tehran, and spent a few days with the Chindit commander Orde Wingate whom he thought ‘quite mad’. Antony Eden said to him – ‘I have heard all about you’ (the story of Snipe had been in the papers). When in the desert, he would be sent for by his Commander-in-Chief, Wavell, to join his family for charades, which impressed his brother officers.

In later years he was the subject of articles and documentaries – even a novel (Alamein by Iain Gale, 2010) in which he is the hero (‘Killing had become second nature to Bird…’ says the silly jacket blurb). Bird retired in 1985 ‘when bricks went metric’ as he put it, although he did the occasional design for a friend, like the millennium folly he built for Sir Alistair Horne in Turville. He never lost his love of gardening, sketching or whisky at 6.45. Aged 97 he was asked by his doctor how much he drank and he said: ‘two or three beers at lunch, whisky and perhaps 4 glasses of wine in the evening.’ ‘Far too much!’ exclaimed a horrified doc. Bird replied – ‘I’m fucking 97!’